A woman in early labour immersed in days of sexual play re-discovering the sensations of her body. A woman in labour wearing nothing but a black modal jersey dress swaying back and forth gripping a red silk rope. A woman in active labour on all fours undulating with her contractions in a bathtub while midwives pour water on her back.

My memory keeps me as all of these women.

Coming up on the 1 year anniversary of O—’s birth and curious for the perspective of young adults, I screened Stan Brakhage’s silent lyrical film Window Water Baby Moving (1959) last semester.

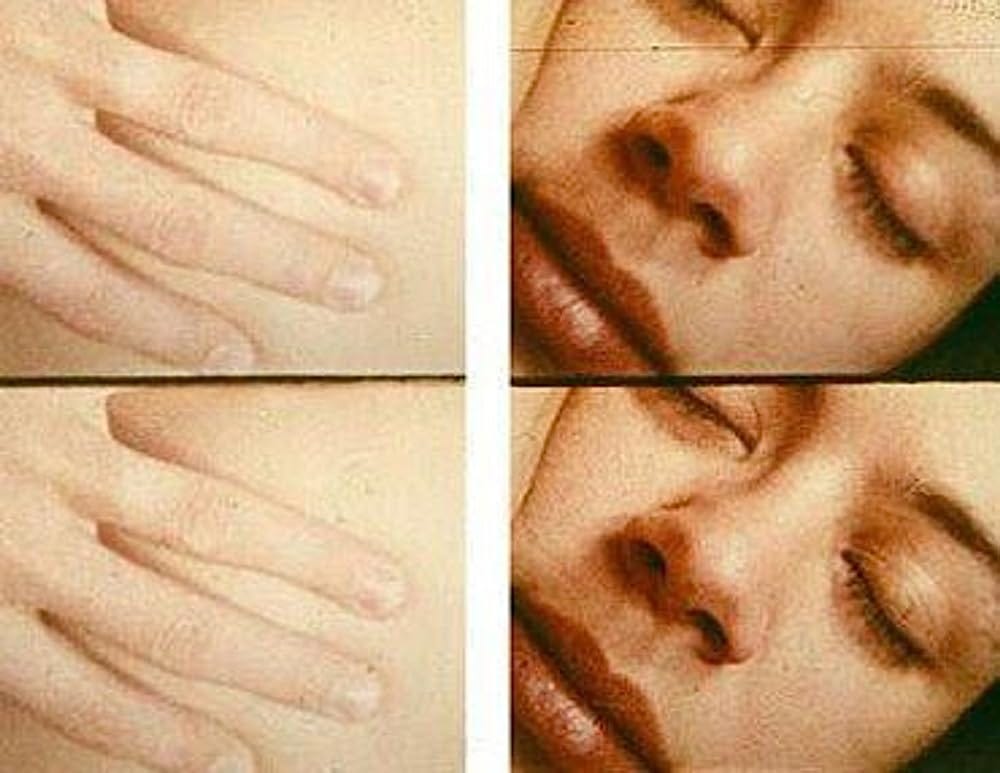

The film documents the birth of the director's first child, Myrrena, by his then-wife Jane. The film starts with the image of Jane’s full belly as she reclines in a bathtub. Then comes a sequence focused on the birth. We see the literal emergence, in extreme close-up, of his newborn daughter. The film does all of this without music or sound of any kind, which makes the experience both confrontational and strangely serene.

I first encountered Brakhage in Phil Hoffman’s Experimental Cinema course at York, and became obsessed with his oeuvre, especially how fitting it was to VJ with, something I was doing regularly at the time. In my late 20s, children had no space in my endless sexual desires, so the childbirth was secondary to the film’s editing of Jane’s sensuality. Jane was 22, younger than I was, when I first saw her, and over a decade younger than when I had my first child.

As I re-watched it in 2023 before showing it to my class, I still wanted be there with Jane, run my fingertips over her orgasmic smile and glowing skin, transfixed by her moves. Brakhage’s editing captured those possibilities. I became the smitten audience projecting onto a woman like, as a feminist, I’m not supposed to. Whatever. I’m aroused, not by her, but by the memories of my body’s capabilities.

I’m lucky to have two births I loved, despite their excruciating pain and because of it. The pain of childbirth and the “ring of fire” of vaginal birth is beyond pain, and it also made my experience.

Fitting that the expression for when the baby’s head crowns is called “ring of fire”1 —a condensation of nature in one acute moment that has a seemingly endless durational intensity.2

Many birthing people are disturbed by the reverence for pain toxic white wellness communities espouse. I am too. In 2015, I bought Spiritual Midwifery when I was pregnant with S— and stopped after about four pages. My neighbour, M— who hates giving birth, yet has had four unmedicated births, was shocked at how chill and awesome it was to get an epidural; a decision she made with her fifth. I’m grateful she had a spectrum of choices on what to do with her body.

Having a choice means it’s also okay to revel in the spectrum of your childbirth’s possibility and its concomitant sensations without making yourself a martyr of suffering.

I love that my body was able to rupture the corporeal boundaries I have in everyday life. I’m not a risk taker, I’m afraid of heights, but the surrealism of childbirth analogous to a salvia trip where planes of existence expand and merge simultaneously is a thrill I desire despite my screaming otherwise in the moment.

The pain produces a “beyond presence” in active labour—the part where contractions are about 1 minute apart, no more chilling and chatting, and birth is most likely on the way. Both times, near the end (although I didn’t know it was the end until I read through the charts my midwives filled out), I was somewhere else and in the birthing centre’s turquoise “Ocean Room.” A room both of my children were born in 6 years apart.

I was the world.

With S—, my entire back slowly cleaved to take in the universe,

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Near to The Wild Heart to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.