Palestine & the Persistence of Childhood Innocence

on Palestine and the boundary between a genuine shielding our children from the brutality of the world and the reproduction of the myth of innocence

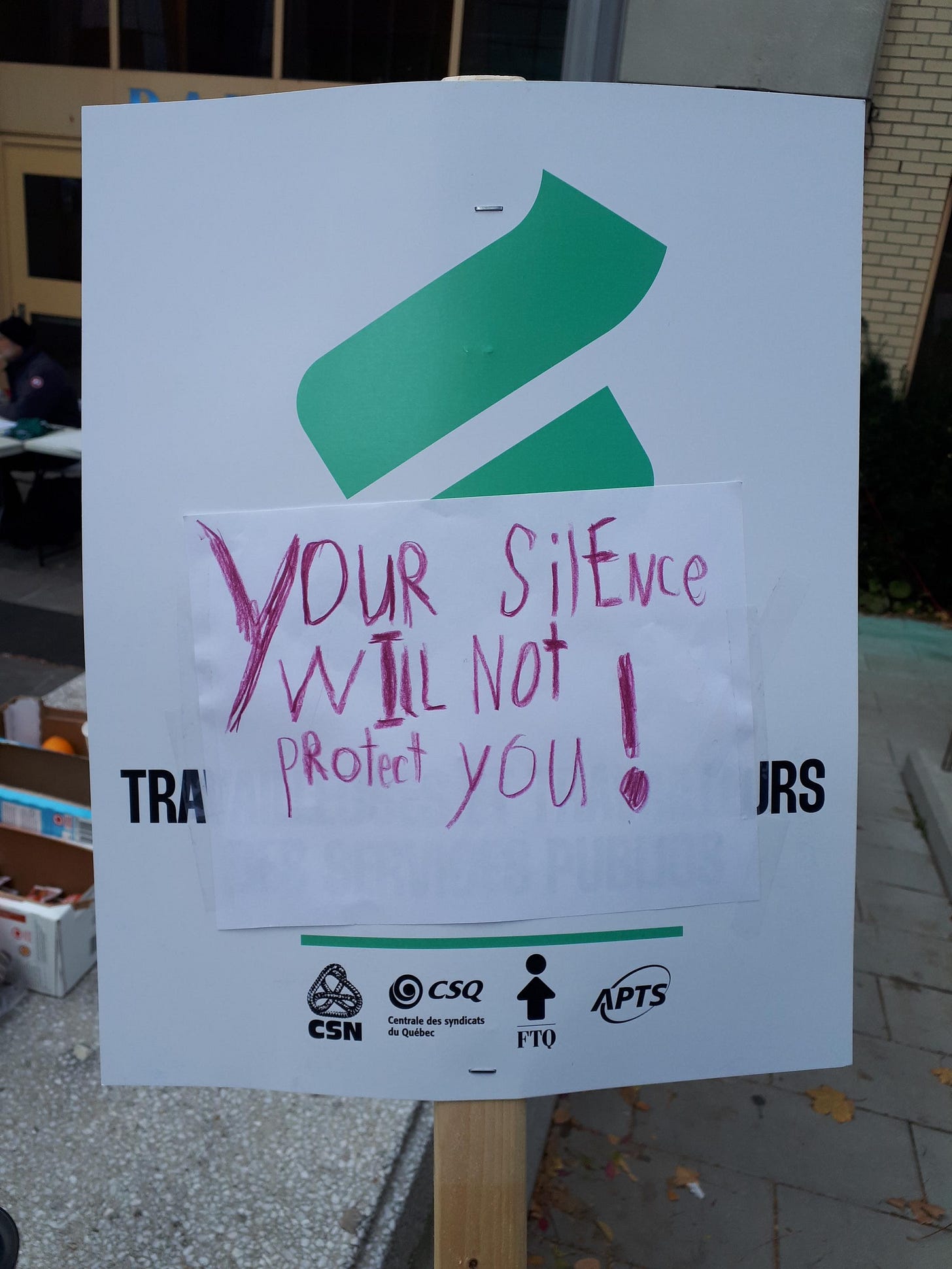

“Is that child dead?” S– asks me, his eyes wide, pointing to a placard someone is holding. The placard is covered with a large photo of a child lying on the ground in their blood. Above the photo is a phrase about genocide.

“Yes.”

S– looks at me and looks back at the placard as we march down the southbound lanes of Parc Ave under the abundant sun surrounded by Palestinian flags and keffiyehs.

It’s October 2023.

The encounter—a recognition that violence is brutal, possible, and real—can be read as an image of “innocence lost,” a shaky concept when a child becomes aware (conscious?) of something outside their mythical utopian condition. A condition that, according to Foucault, has a long historical tradition in Western social, political and scientific institutions, and is in turn, reproduced by us.

At the end of December, Rupert Common, S–’s breakdancing teacher, proposes the class finish the term with a dance for the kids in Gaza. Several of the parents are shocked: “How can you assume they even know what is going in Gaza?”

S– speaks up, “Well, I do!”

I observe the room silence him before I speak up.

The parents, like squirrels chasing each other over detritus, squawk the revisionist history cliches of peace, love, and unity.

Months later, I ask my therapist what an appropriate boundary is between a genuine shielding our children from the brutality of the world and the reproduction of the myth of innocence.

For Foucault (1981), the persistence of childhood innocence as an untouchable construct and ‘true’ discourse is ‘both reinforced and renewed by a whole strata of practices, such as pedagogy, of course; and the system of books, publishing, libraries; learned societies and laboratories.’ The desire to define ‘the’ innocent child emerged out of a ‘will to know which... sketched out schemas of possible, observable, measurable, classifiable’ knowledge (Foucault, 1981, p. 55).”1

To uphold this antagonistic world, the child needs to be understood and treated as a tabula rasa for the adult’s expectations and projections, contrary to the way children grow into the world, as my hero, Maria Montessori notes. The child, specifically the middle-class white child, is positioned as the site of hope and social transformation—2 “Think of the Children!” go, go, go.

This fallacy affirms a hierarchical dichotomy between adults and children, in which the adults “know best” and must “regulate” children. It also allows for the positioning of some children as innocent, and others as a priori transgressed.

The clearest indication of this schema is how Israel’s PM, Netanyahu, describes the Israeli children versus the Palestinian ones: “This is a struggle between the children of light and the children of darkness, between humanity and the law of the jungle.”3 He repeats a similar statement in a televised address (below), as do many Zionist’s in their unhinged TikTok videos.

To uphold the ideology of innocence this distinction also needs to be circulated by the media. Like a newscaster’s linguistic acrobatics describing the murder of a preschooler by the IDF in Gaza: “Accidentally, a stray bullet found its way into the van … and that killed a 3 or 4-year-old young lady."

The blatant passive voice that blames the van leaves the audience with the opening and closing of the remark: there was an accident, and a young lady was killed.

Garlen et al (2021), argue, that “by the late 19th and early 20th centuries, this doctrine of innocence came to operate as a regime of truth for modern Euro-American society”, of which I see Israel as a direct result.

Unlike Maria Montessori, who says to “follow the child.”

I return to my ambivalence about S–’s encounter with the placard. He bore witness to it. There is no going back. There is the opportunity to observe what has changed inside him. Perhaps it was less “an innocence lost” but a fracture? For S, it witnessing something that had been abstract to him; I have told him about the murder of children, but now he had an image to imagine. How does murder look like? In his mind, it has been very old people that die, not children. Now, death is a reality for someone like him. Is this why My Girl traumatized many of us?

Here, on the placard was a photo of a kid, that could be his age—martyred. S–, at 7, is already older than my experiences with violence in Poland, but maybe he is still too young? The families and their children have no choice. Is the age of innocence bound to geography?

The encounter happened at the first march/protest/sit-in of many we attended over the fall turning into winter. This time it was just me and S, meeting up with my friend Sarah and her family.

Other times we take O–, who loves crowds and the attention of the public. S– has taught her how to chant, “Free free Palestine,” which she does around the house, too.

It never stops being unsettling to wilfully walk chanting for an end to genocide and a free Palestine, knowing that simultaneously children are forcibly walking to evacuate from their shelters and running away from bombs.

The dehumanization of Palestinians, including children, began even before the 1948 Nakba, and certainly before October 7.

The children are always ours, every single one of them, all over the globe; and I am beginning to suspect that whoever is incapable of recognizing this may be incapable of morality.—James Baldwin, 1980

I ask S– how he’s feeling about seeing that image. It makes him upset to know there are people who kill children who didn’t do anything wrong: “Even if you do something wrong, you shouldn’t be killed!”

A few days later, S– tells me he is feeling a lot of feelings in regards to people being killed in Palestine. Is it because I am constantly talking about it, and making links to other genocides in the world? Every day is a lesson in figuring out how to talk about it just enough but not too much.

My friend K– and I take S– and her daughter, A– to see Wardi (2018) at Cinema Public, a beautiful animated film about Wardi, an 11-year-old Palestinian girl who lives with her family in a Lebanese refugee camp. I had watched it with S– at home in advance, to judge is appropriateness, and have the ability to pause or shield his eyes, which I did. During the film, S– warned A– before each of the two scary parts, but she was sure she could handle it.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Near to The Wild Heart to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.