Naming as the Basic Unit of Verbal Behavior

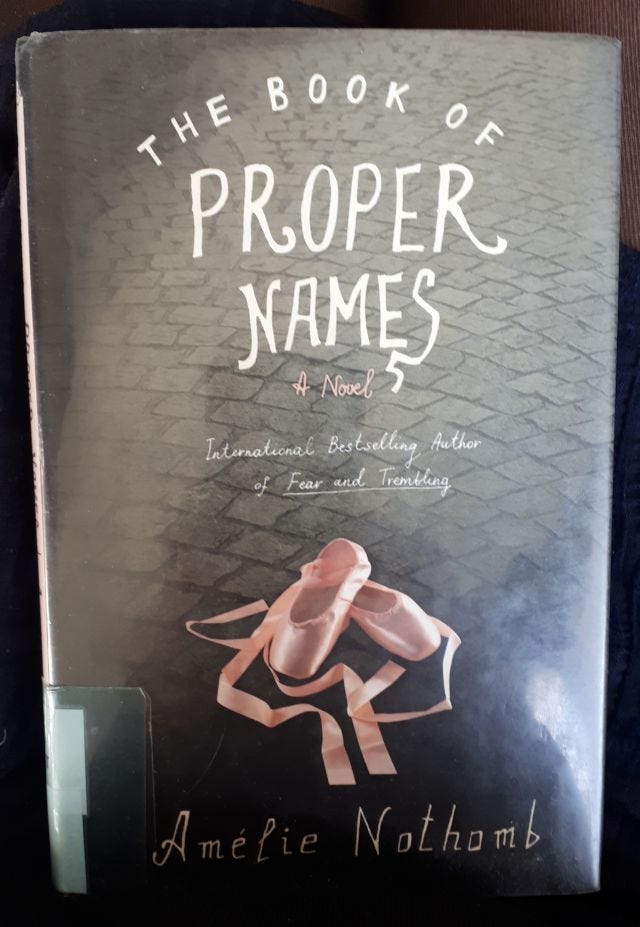

Earlier in the fall when we hadn’t yet began a search for a baby name—avoiding the acceptance of newborn care—a book spine with a handwritten typeface caught my attention. It was thinner and smaller than the surrounding books using bold bright capital letters. Despite having gone through (i.e., borrowed but not read) many of the English fiction books since Marc Favreau was mainly a francophone library, I didn’t recognize the author or the book. Its title, The Book of Proper Names, and book jacket synopsis were written to me, surely.

“To have an extraordinary life, Lucette [the mother] believes, one must have an extraordinary name. Horrified by the pedestrian names her husband chooses for their unborn child (Tanguy if it's a boy, Joelle if it's a girl), Lucette does the only honorable thing to save her baby from such an unexceptional destiny - she kills her spouse.”

Lucette and I come with the weight that “naming is a parent’s first sorcery,” as Tiphanie Yanique in Land of Love and Drowning (2014) writes.

Our late cat—named by me and my partner who shares my hyperbolic destiny—lived up to his extraordinary name: Ruffneck Bijoux Clyde Softilicous Cuddlesworth III. Even with his diminutive as Ruffie, we used all five names regularly depending on his mood. Amelie Nothomb, the author of The Book of Proper Names, was born Fabienne Claire Nothomb.

When I was pregnant with S—, much about the responsibility of naming came my way. When we name something we give it a meaning—we signify it—bracket it as a thing that exists in relation to us. Julia Kristeva in Revolution in Poetic Language posits that the writer as the subject-in-process and the signifying process work together: both naming and being named. The parent that names is also (re)named. I am signified as a mother when I have a child. We now exist as those names to each other.

Call me by my name, do something. Be something.

Speaking or writing a name conjures up an image, a history, a sense of personal style.

2015/2021

S— loves his name. He doesn’t even have any nicknames. None have fit nor does he like being called anything but. Its two syllables don’t warrant a nickname. A diminutive would change the name and its meaning completely. S— always wants to be called by his name.

Sociologist Karen Finch writes that our name “marks us as a unique individual, and it also gives some indication of our location in the various social worlds which we inhabit – it encapsulates our legal persona as a citizen, it reveals our gender and probably our ethnicity.”

In Quebec “if you gave your child any name that is unusual or that might cause your child to be ridiculed or not taken seriously, the Directeur might ask you to choose a less controversial name. If you refuse to change the chosen name(s), the matter could wind up in court where a judge will make a final decision.”

The Book of Proper Names, a cruel hope, only served to add to the weight of naming responsibly. Before killing herself, Lucette names her daughter Plectrude. Plectrude grows into her name (but not its history) with a tormented life. Her world cannot handle her so it imposes a slow death. I want to give my child a name that is a world to grow into; that has a curious history yet doesn’t preclude a life by them inhabiting it.

My mother grieves my given name. Not Flora after her favorite singer, but Magdalena, a generic Polish name. A name she was bullied into giving me. A name I don't do enough with.

The books and articles on naming practices torment me. But I can't stop treating this endeavour like another research project.

Two months after S— was born, I trudged in a snowstorm with leaky snow boots to the government offices with a delinquent birth certificate form and a cheque. We could barely afford the fine in those days; a late fee after the 30-day period a parent has to register a newborn child. We couldn’t find the perfect middle names. 30 days seems so short compared to a life time of bearing a name. And still, S—’s second middle name, named after a Polish poet, has, in our everyday, transformed to the poet’s last name, which means “one who loves,” rather than the poet's first, which, according to my grandmother, connotes a "misogynist bro.”

Give your daughters difficult names. Give your daughters names that command the full use of tongue. My name makes you want to tell me the truth. My name doesn’t allow me to trust anyone that cannot pronounce it right.

—Warsan Shire

A name pronounced is the recognition of the individual to whom it belongs.

He who can pronounce my name aright, he can call me, and is entitled to my love and service.

— Henry David Thoreau

Alongside a compendium of girl's names, we had at least found S—’s first name several weeks before he was born. A 5-letter simple and rare first name that has a history we stand behind and moves with flourish at the tip of my Pentel Sign Pen. An unassuming lead up to a name comprised of 44 letters; an overrun of characters that has stopped me from booking airplane tickets online. The full name doesn’t fit within conventions. Most booking sites online have a limit of about 30. In the end S-’s name ends up truncated anyway. He is too big of a world to exist fully across borders.